Most Americans know that Thomas Jefferson was the author of the Declaration of Independence, president of the United States, and an important voice for freedom and individual rights in the formation of the United States of America. What’s important to understand is that all the Founders were well-educated men who read all the crucial philosophers of their day and used that knowledge to debate the possibility of self-government.

Most Americans know that Thomas Jefferson was the author of the Declaration of Independence, president of the United States, and an important voice for freedom and individual rights in the formation of the United States of America. What’s important to understand is that all the Founders were well-educated men who read all the crucial philosophers of their day and used that knowledge to debate the possibility of self-government.

It’s difficult for today’s Americans to understand how radical an idea self-government was in the late 18th century. Most Western powers were monarchies because few of the ruling class (those with assets) trusted the masses to choose a government. The few experiments in democracy from antiquity were considered failures by the American revolutionaries. When people realized that they had a majority, they might vote to remove money from the smaller in number wealthy classes and transfer that money to themselves. Since money is power, the powerful decided they did NOT want a system that could enable the majority (mostly poor) to simply vote to play “Robin Hood.”

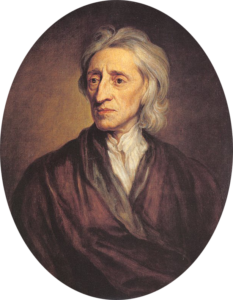

John Locke had a solution: create a government that enabled rights, but also limited the power of government. Since property was the essence of wealth in Locke’s day, the key was to limit governments’ ability to separate your property from you and give it to someone else. Locke put the issue succinctly: government should be used chiefly to protect life, liberty…and property. Where have we heard that before? Jefferson’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” was a less money-grubbing way to make the case for the protection of the assets of the American gentry. It was the gentry class, those with land, that had the most to gain from the American independence that Jefferson’s document was advocating. Their intent was to promote a system of government that enabled anyone to someday achieve the success that they had achieved by carving a business out of the wilderness in the New World.

Locke’s theory of self-government also entailed what has been known as the contract theory of government. People choose representatives to create laws, collect taxes, and provide services and infrastructure that benefit those taxpayers. As long as they are responding to the needs of the voters, the representatives can keep their jobs. That represents a contract between the voters and the government. If they break that contract— vote laws the voters don’t like— the people have to the right to fire them, and in extreme cases, overthrow them. In Locke’s lifetime, England had experienced civil war, the execution of the king, parliamentary rule, restoration of the monarchy, etc. He even fled to the Netherlands for a short period of time because his views put his life in danger. His philosophy was not just theory to him, but something that had life and death consequences.

This is an important difference in the attitude Americans have regarding their government. Once in a while, they remember that THEY are the boss. Their elected representatives are employees NOT the other way around. “Government money” is actually the people’s money that has been acquired through taxation, fees, etc. It’s the people’s money. It does NOT belong to “the government.”

Americans can be very generous but don’t like being taken for granted. As any individual would, they want to make sure that the money spent is well-used, accounted for, and properly appreciated. Great examples in the past are the Marshall Plan, the rebuilding of Germany and Japan after World War II, and projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority, Hoover Dam, and educational assistance. It’s when they see money wasted, fraudulently used, or spent in ways that were dishonestly sold to the voters that they use their freedom of speech to speak out. The American voter will then say “enough!” and produce a surprise at the voting booth. In those instances, voters innately sense that the “contract” has been broken, and the resulting “overthrow” tosses out individuals, and sometimes a political party is “set straight.” This is a bi-partisan practice that we celebrate from time to time in a little process we call an “election.”

Next up: a second version of “contract theory.” A little gift from France…